Processing Images out of Telescope Data

Published sometime in 2016, when I was 16

So I’m posting after a year maybe. Meanwhile, I’ve become more interested in music, photography, and astronomy. Deep sky astrophotography as a hobby isn’t affordable or accessible to me (and many of us), since it requires telescopes and tracking mounts and specialized cameras to get the kind of results I want. Fortunately, Hubble Space Telescope and some other observatories release data for amateur astronomers and scientists to use. Among other things, you can use it to create truly stunning images of the heavens.

To create images out of Hubble Space Telescope data wasn’t what I initially thought it’d be. It’s not like you download an image and process it. There is a learning curve, but the process is fairly easy after you get a hang of it.

Getting the data

Hubble and other telescopes actually capture images through different filters at different wavelengths. The raw data is grayscale, so you need to “combine” multiple images to create a final color image.

The data is in a special “fits” format, which is used particularly for scientific use thus most image processing programs don’t directly support it. To convert the fits files into uncompressed .tif format you need a program called “FITS Liberator.” It’s small and fairly simple to use. You can also select the stretch function if you need more dynamic range, and you also have some other useful options to play with.

Processing it!

I combined the grayscale images by using them as layers in Photoshop with Blend mode -> Screen. “Coloring” the image was done by colorizing hue adjustment with a clipping mask for each layer. You can use any set of values for hue, and in many cases the filter wavelength is greater/lesser than that of human eye, so the color in most cases is “false.” IMHO this is okay, because our eyes weren’t exactly evolved to see the beauty of universe, so we can only see a fraction of emission of this universe, and it really isn’t “cheating.”

Figuring out the correct set of hue values is tough. There are several other adjustments that are to be made for creating an aesthetically pleasing image. Curves and levels are two my favorites.

Some of the images I processed

The Antennae Galaxies

These are the colliding Antennae Galaxies. Think about it again, they are two colliding galaxies. The Milky Way galaxy is also going to collide with Andromeda galaxy, which is racing towards us at a speed of 250 000 mph. This image was created out of three different filters, and this was my first image processed out of Hubble Space Telescope data. Believe it or not, I a

lmost spent the whole day working on this image.

The Andromeda Galaxy

This is the great Andromeda Galaxy, the Messier 31. It is (only?) 2.5 million light years away from us. This is the visually the largest galaxy in the night sky, about six times the diameter of full moon in the night sky. The original images are 47MP in resolution, which is a lot. So I had to convert the original FITS files into relatively low-resolution images, process them, and then open up the full resolution images in Photoshop and use the numbers from the earlier processed images to create a final images. The results turned out great. This image is made of three different grayscale exposures as well.

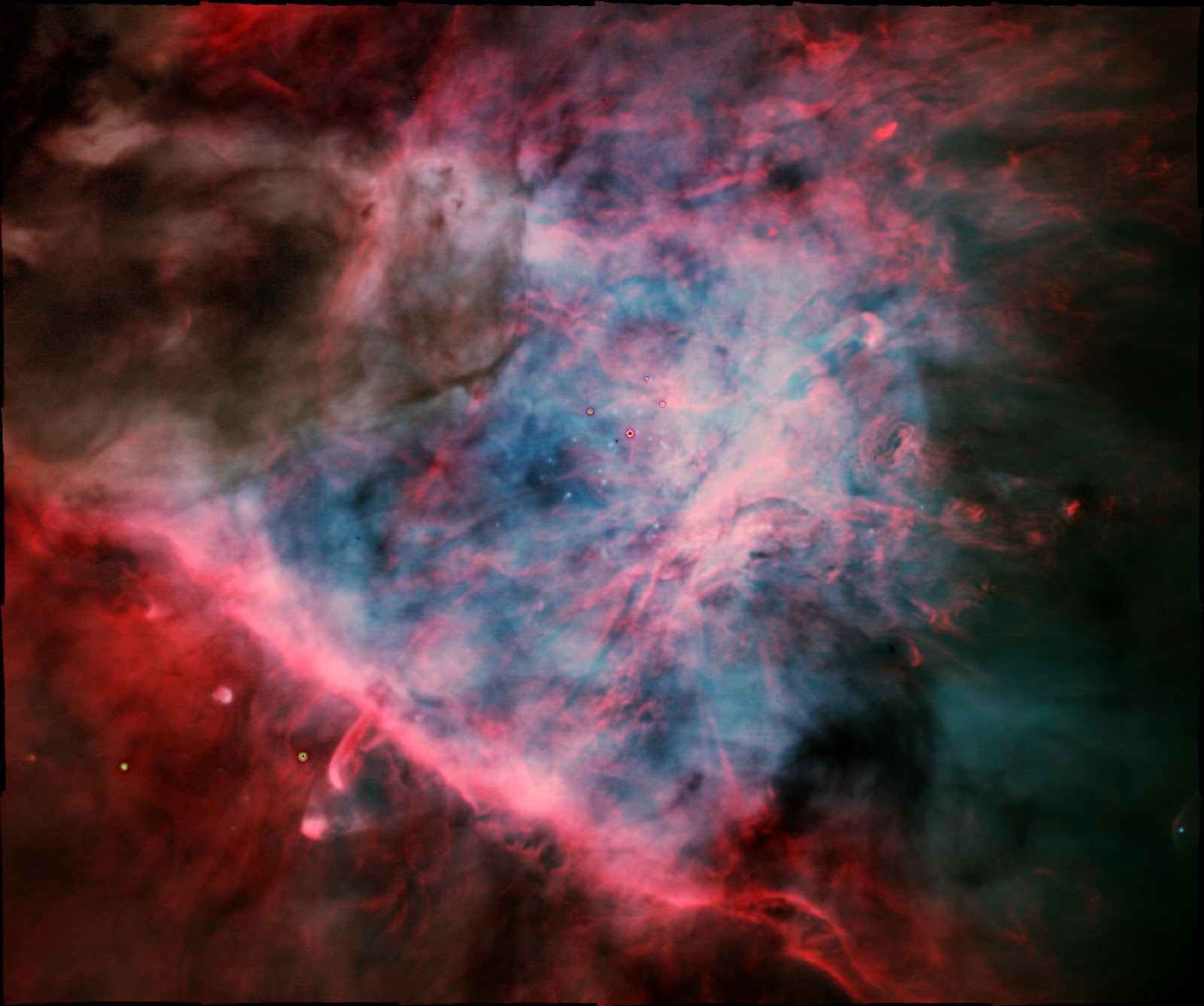

The Great Orion Nebula

This is the great Orion Nebula, the Messier 42. It’s one of my favorite things in the night sky. I processed this image after realizing that Hubble is not the only telescope that releases its data, and that earth-based telescopes can make truly awesome images of the night sky as well. Unlike the previous images, this image is made of four different exposures, chosen out of several available exposures by plain trail and error. The color of this image, especially at the core, is a little bit like “true color”, although the data for this image wasn’t captured at “true color” wavelengths.

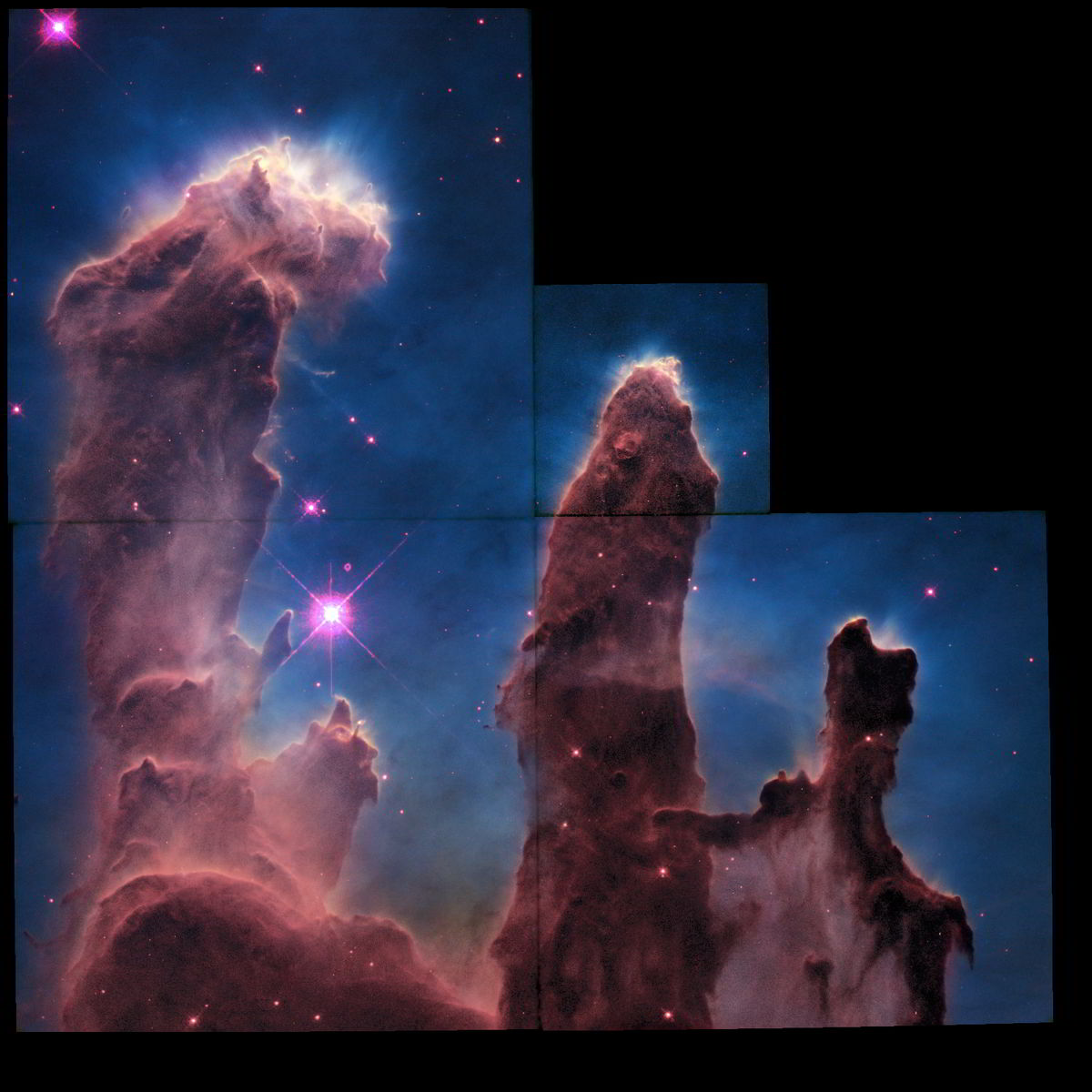

The Pillars of Creation (Eagle Nebula)

These is the “Pillars of Creation” part of the Eagle Nebula. This is arguably the most famous of Hubble images. A single tower of gas in the picture is approximately 90 trillion kilometers in height. This image was processed when I became more skilled in image processing. It took 3 hours of processing time, but the results turned out to be fairly worth the time.